The alertness in determining early possible kick indicators in well control is of the utmost importance to prevent a well control incident. Careful observance and positive reaction to these signs will keep the well under control and prevent the occurrence of a well control situation.

The various signs that have been recorded as early warning indicators are not consistent in all situations. The signs however may have to be used collectively as one indicator may not accurately provide the warning of getting into an underbalanced situation. Even though the series of signs may change between wells, early warning indications can be found from the following list.

- Increase in drilling rate of penetration.

- Increase torque and drag.

- Decrease in shale density.

- Mud property changes.

- Increase in cutting size and shape.

- Increase in trip, connection and/or background gas.

- Increase in the temperature of the return drilling mud.

- Decrease in D-exponent.

Increase in Rate of Penetration When drilling ahead and using consistent drilling parameters, as the bit wears, a normal trend of decrease penetration rate should occur. If the differential pressure between the hydrostatic pressure of the drilling fluid and formation pore pressure decreases, an increase in the drilling rate occurs as the chip hold down effect is reduced.

A general and consistent increase in penetration rate is often a fairly good indicator that a transition zone may have been penetrated. This change in rate of penetration is known as a Drilling Break (Figure 1). A rapid increase in penetration rate may indicate that an abnormal pressure formation has been entered and an underbalance situation has occurred.

Figure 1 – Drilling Break

Increased Torque and Drag

Increased drag and rotary torque are often seeb when drilling into overpressured shale formations due to the inability of the underbalanced mud density to hold back physical encroachment of the formation into the wellbore.

Drag and rotating torque are both indirect and qualitative indicators of overpressure. They are also indicators of hole instability and other mechanical problems. Torque and drag trend increases often indicate to the driller that a transition zone is being drilled. Up drag and down drag as well as average torque figures should be recorded on each connection. These trends are valuable when comparing other trend changes.

Example of relevant information can be found on the following articles;

Hydro-Pressured Shale Causes Stuck Pipe

Geo-Pressured Shale Causes Stuck Pipe

Decrease in Shale Density

The density of shale normally increases with depth, but decreases as abnormal pressure zones are drilled. The density of the cuttings can be determined at surface and plotted against depth. A normal trend line will be established and deviations can indicate changes in pore pressure. Shale density can be measured by using a mud balance so please see more detail in this article, Bulk Density of Cuttings Using Mud Balance.

Increase in Cutting Size and Shape

In transition zones or in abnormally pressured shale’s (sandy shale’s and bedding sand streaks) the shale’s break off and fall into hole because of under balanced condition (pore pressure greater than mud hydrostatic pressure). Water wetting may further aggravate this problem.

Changes in the Shape of Shale Cuttings can occur as an underbalanced situation is developing. The particles are often larger and may be sharp and angular in the transition zone. Extra fill on bottom may coincide with the trend change. Severe sloughing will often cause changes in pressure and stroke relationship. Hence, it is very imperative to frequently check cutting coming over shale shakers (Figure 2) to monitor a wellbore behavior.

Figure 2- Always check cutting size over shale shakers

Normally pressured shale’s produce small cuttings with rounded edges and are generally flat, while cuttings from an over pressured shale are often long and splintery with angular edges. As reduction of hydrostatic differential between the pore pressure and bottomhole pressure occurs, the hole cuttings will have a greater tendency to come off bottom. This can also lead to shale expansion causing cracking, and sloughing of the shale into the wellbore. Changes in cuttings shape and cuttings load over the shakers needs to be monitored at surface.

Mud Property Changes

Water cut mud or a chloride (and sometimes calcium) increase that has been circulated from bottom always indicates that formation fluid has entered the wellbore. It could be created by swabbing or it could indicate a well flow is underway. Small chloride or calcium increases could be indicative of tight (nonpermeable) zones that have high pressure.

In certain type muds, the viscosity will increase when salt water enters the wellbore and mixed with the mud. This is called flocculation because the little molecules of mud solids, which are normally dispersed, form little “groups” called flocs. These flocs cause viscosity and gel increases. In other type muds you might see a viscosity decrease caused by water cutting (weight decrease). This is true when operating with low pH salt saturated water base muds.

In oil based mud, any water contamination would act as a “solid” and cause viscosity increases. Gas cut mud would be fluffy and would have higher viscosities (and lower mud weight). It is essential to know that the Trend changes are more important than the actual Value of the change.

Increase in Trip, Connection and Background Gas

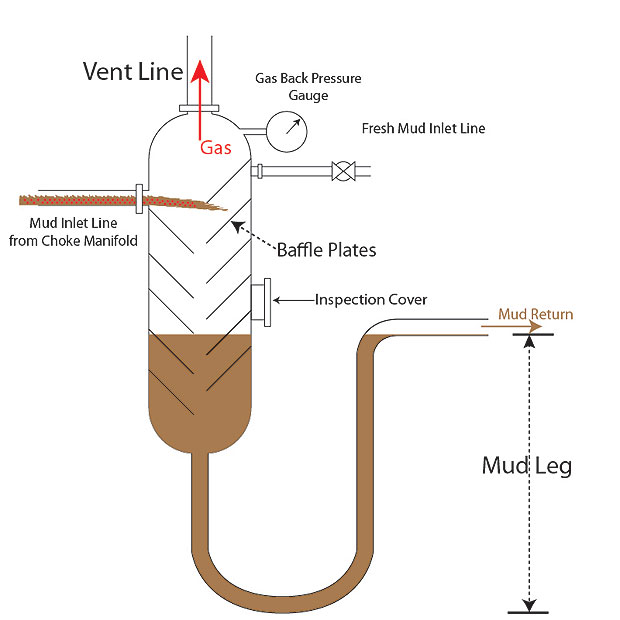

Return mud must be monitored for contamination with formation fluids. This is done by constantly recording the flowline mud density and accurately monitoring gas levels in the returned mud.

Figure 3 – Gas Monitoring at a Return Line

Gas cut mud does not in itself indicate that the well is flowing (gas may be entrained in the cuttings). However, it must be treated as early warning of a possible kick. Therefore pit levels should be closely monitored if significant levels of gas are detected in the mud. An essential part of interpreting the level of gas in the mud is the understanding of the conditions in which the gas entered the mud in the first place. Gas can enter the mud for one or more of the following reasons:

- Drilling a formation that contains gas even with a suitable overbalance.

- Temporary reduction in hydrostatic pressure caused by swabbing as pipe is moved in the hole.

- Pore pressure in a formation being greater than the hydrostatic pressure of the mud column.

Gas due to one or a combination of the above, can be classified as one of the following groups:

Drilled Gas When porous formations containing gas are drilled, a certain quantity of the gas contained in the cuttings will enter the mud. Gas that enters the mud, unless in solution with oil base mud and kept at a pressure higher than its bubble point, will expand as it is circulated up the hole, causing gas cutting at the flowline. Gas cutting due to this mechanism will occur even if the formation is overbalanced. Raising the mud weight will not prevent it. It should be noted that drilled gas will only be evident during the time taken to circulate out the cuttings from the porous formation.

Connection Gas Connection gases are measured at surface as a distinct increase above background gas as bottoms up occurs after a connection. Connection gases are caused by the temporary reduction in effective total pressure of the mud column during a connection. This is due to pump shut down (i.e. loss of ECD) and the swabbing action of the pipe. In all cases, connection gases indicate a condition of near balance. When an increase trend of connection gases are identified, consideration should be given to weighting up the mud before drilling, operations continue and particularly prior to any tripping operations.

Trip Gas Trip gas is any gas that enters the mud while tripping the pipe with the hole appearing static. Trip gas will be detected in the mud when circulating bottoms up after a round trip. If the static mud column is sufficient to balance the formation pressure, the trip gas will be caused by swabbing and gas diffusion. Significant trip gas may indicate that a close to balance situation exists in the hole.

Change in the Temperature of the Mud Returns

The temperature will normally take a sharp increase in transition zones. The circulating rate, elapsed time since tripping and mud volume will influence flowline temperature trends. The temperature gradient in abnormally pressured formations is generally higher than normal. The temperature gradient decreases before penetrating the interface and therefore marked differences can give and early indication of abnormal pressures. This is usually a surface measurement which has a tendency to be influenced by operating factors. Figure 4 shows plots of temperature increase while penetrating an abnormal pressure formation.

Figure 4 – Increase in Flow Line Temperature (Slide Player, 2016)

Decrease in D–Exponent

The D-exponent will be plotted by the well loggers and maintained current at all times. This value was introduced in the mid sixties to calculate a normalized penetration rate in relation to certain drilling parameters.

The “d-exponent” described from the equation below:

d = log (R ÷ 60N) ÷ log (12W ÷ 1000D)

Where; R = penetration rate in feet per hour

d = exponent in drilling equation, dimensionless

N = rotary speed in rpm W = weight on bit in kilo pound

D = bit size in inch

** Note: this equation is is valid for constant drilling fluid weight.

The D-exponent may be corrected and normalized for mud weight changes and/ or ECD (equivalent circulating density) by the following:

dc = d x normal pressure (ppg) / mud weight or ECD (ppg)

A plot of Dc-Exponent versus depth in shale sections has been used with moderate success in predicting abnormal pressure. Trends of Dc-exponent normally increase with depth, but in transition zones, its value decreases to lower than expected values which indicate a possible high pressure zone. Figure 5 demonstrates a Dc-Exponent plot showing an abnormal pressure ramp.

Figure 5- Dc-Exponent Plot

References

Cormack, D. (2007). An introduction to well control calculations for drilling operations. 1st ed. Texas: Springer.

Crumpton, H. (2010). Well Control for Completions and Interventions. 1st ed. Texas: Gulf Publishing.

Grace, R. (2003). Blowout and well control handbook [recurso electrónico]. 1st ed. Paises Bajos: Gulf Professional Pub.

Grace, R. and Cudd, B. (1994). Advanced blowout & well control. 1st ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

Watson, D., Brittenham, T. and Moore, P. (2003). Advanced well control. 1st ed. Richardson, Tex.: Society of Petroleum Engineers.

Slideplayer.com. (2016). Lesson 21 Prediction of Abnormal Pore Pressure – ppt video online download. [online] Available at: https://slideplayer.com/slide/8617461/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2019].

Drilling Formulas and Drilling Calculations. (2009). D Exponent Calculation. [online] Available at: http://www.drillingformulas.com/d-exponent-calculation/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2019].

The post Possible Kick Indicators in Well Control appeared first on Drilling Formulas and Drilling Calculations.

Figure 3 – Pipe Rams Cameron U Type (Courtesy of Cameron)

Figure 3 – Pipe Rams Cameron U Type (Courtesy of Cameron)